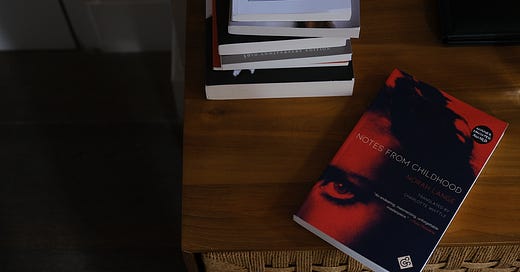

je lis trop: notes from childhood

reading Norah Lange's words and coming back to childhood memories

“I can’t remember which book or comment led me, for a few days, to feign a serious mood, a solemn and pensive attitude. When my sisters called me to play, I answered in a tone of concentration, ‘I can’t. I have too much to think about.’”

Who’s Norah Lange? Before writing this essay, I spent some time looking her up online. Not much info to be found—there’s laughingly little about her on Wikipedia or anywhere else. She was born at the end of October in Buenos Aires in 1905. She had Norwegian roots. She was associated with the Buenos Aires avant-garde movement of the 1920s and 1930s. She began by writing poetry. Her husband was a poet. Jorge Luis Borges liked her. She had a flamboyant personality and was a little eccentric. She hosted literary gatherings. She won some prizes.

Many of these modest descriptions of her life are accompanied by the same portrait, a black and white photograph of Lange. She’s resting her chin on her hand, looking at something or someone we can’t see. A fragment of this portrait can also be seen on the cover of Notes from Childhood.

Two of Lange’s books have been translated into English. People in the Room, written in 1950, was the first (it was published in English only in 2018). It is a mysterious, introspective novel about an adolescent girl who spies on three older women and finds a way, unlikely as it is, to step into their story. But the line between the real and the imagined is unclear. I read the book last year and liked it—I have a taste for plotlessness and unreliable narrators—yet I didn’t return to it in my thoughts afterward.

But I fell in love with Notes from Childhood.

I must admit that the title of Notes from Childhood didn’t exactly thrill me. Out of autobiographical material, one, perhaps, always expects a little fanfare—a collection of highlights, all the tedious bits sped up or trimmed down. I, as a reader, should relish the most shining parts. And this is a book on her childhood, a book whose back cover promises scenes of domesticity. Wouldn’t this be just a little bit boring?

I was also still influenced, even if just a little, by my former outlook toward childhood. For quite some time, I thought that childhood was… well, not necessarily the most boring time, but perhaps nothing worth looking at. Once I turned fifteen or sixteen, I thought the childhood chapter was definitely closed. I was happy to be an adult, finally an adult. I treated childhood like a carefully sealed time period, almost a museum relic. I saw clear borders between the years and believed nothing ever could spill over. There was such a strange finality to my feelings.

But at some point in the recent months, I realized how much of my instincts, ways of thinking, and behaviors ingrained within my heart and mind date to those “museum-relic” years. There is no seal, there is no lid that could contain my childhood. I’m carrying it with me all the time. It is a powerful revelation, one that left me bewildered.

In this book, Lange seems to be an introspective, playful, rebellious girl. She's a little observer of her surroundings, the people, and herself. She describes her parents, sisters, teachers, and others she might've seen in her childhood.

Her memories are laid down in vignettes, snapshots, most of them two pages at max. I appreciate the focus and brevity of the format—I feel it's faithful to how life unfolds. There's no attempt to weave one coherent narrative. Blank spaces let the reader rest and switch from one memory to another while accumulating information about the person who writes.

To be an observer is a compelling role (it’s one of my favorite ones). As a child, observing is a complex undertaking. It feels like groping in the dark without understanding its full breadth and depth. As adults, we must operate with incomplete information, even more so as kids, just because we know so little. We learn things inch by inch. We have strange obsessions and intuitions; we selectively treat the information and arrive at singular conclusions.

Lange's descriptions have strokes in unexpected places. For example, when she remembers her French teacher's daughter, she doesn't focus on her face or behavior. She hyper-fixates on one thing: that she faints. Lange, for some reason, takes this to be an essential trait of a real woman. And she's only interested and fascinated by that girl as long as she knows she faints. How to explain this kind of belief, this kind of obsession?

“Sometimes, I am overcome by nostalgia, the nostalgia caused only by tiny, simple things, by the most unassuming events of all. This is my memory of those Saturday nights, which come back to me on a great wave of gentleness and purity, bringing me the knowledge that my childhood could not have been sweeter.”

I now believe that looking back at childhood memories means looking back at some of the most original, surreal thoughts we've ever had. Lange's snapshots are deeply atmospheric, cinematic.

She remembers perfect Saturday evenings with baths, hot milk, and sisterly conversations. There's something precious about it, like cutting straight to the heart of the life and how it feels when you're happy. Similarly, I remember Friday nights when I watched disco music charts on MTV with my mom. I remember visual things, such as a smokey blue light (where was it coming from? Was it a candle flicker? Was it the light falling from the TV? Was it from the stove?) or a stool beside the table or dancing shadows on the wall.

Lange remembers her little sister Esthercita being born. I remember my brother being brought home from the hospital after his birth. It's my earliest memory. He's dressed in a light blue outfit; my mom is introducing me to him. My hands are gripping the handles of his crib, and I'm looking at the bundle within.

Lange remembers enjoying being sick—she felt as if she were transported to another world. I remember enjoying baths and being hypnotized by the running water. Waiting for the bathtub to fill, I would keep my hand under the tap, watching how the light fell and sparked. A big frosty feeling would fill my imagination.

Lange expertly captures obscure fears and intuitions. For example, she describes her fear of a hand reaching out to her in the dark (she fears the gesture and the intent more than the consequences) and how her sister exploits that fear. This reminded me of how I used to fear lightning. I was always terrified. My mom's reassurance, "Don't worry, you're safe here; it won't reach you," did nothing to me. See, I wasn't afraid of lightning hitting me in my bed or anything like that. It wasn't a fear of physical danger. I was scared of that flash, of that moment when the whole room gets whipped by a blinding light. I couldn't sleep whenever those bolts struck. It was pure visual terror.

Lange remembers many other episodes from her childhood, and I'll leave them for you to discover. They sparkle; they're full of sensory experiences. Talking about such experiences, one more memory of mine, a memory of early childhood holidays by the sea. I remember it would always rain. Because of that, I came to associate the sea with my grey clouds and some kind of disappointment. Also with my blue jacket. When, many years after, I traveled to Greece with my parents and my brother, and I could stand in front of a sparkly sea bathed in sunlight in a lightweight dress, with no grey clouds or jackets in sight, it felt like the stuff of unreality. It felt as if some childhood law was broken, and I felt delighted and mischievous for it.

The translator’s note, written by Charlotte Whittle, mentions that Notes from Childhood was successful because it allowed people to see the eccentric Lange in a more feminine light and in a domestic setting. It allowed people to finally situate Lange in a box of some kind. I don’t know how I feel about that. The so-called domestic scenes feel vibrant and imaginative and alive. I see them truly and honestly as the big stuff, more so than any big adventures.

Though I certainly hope to do something extraordinary one day, I have a feeling that those little emotional flickers, some of which I described above, will be the most cherished moments of my life. The irrational fears, surreal intuitions, and sensory revelations… I’m sure they’ll continue burning bright.

This book went straight to my TBR! I had a similar experience with Patrick Modiano's 'In the Café of Lost Youth' that made me realize how "present" my past, specifically my childhood, has been for me all this time.

I loved these parallel childhood memories, from you and Norah Lange! You always write so beautifully, Monika! 💕

I share the same thought with you regarding the translator, why wouldn't we want to see someone as "eccentric" as they want to be?

And that first quote you shared [...] I can totally relate, from childhood and from life.