I bite into a biscuit with an apple sauce, and a puppy whines. Surely it’s the smell of this sauce that attracts her. She starts licking my fingers, looking for crumbs. I stroke her caramel-colored head and unruly ears while my other hand rummages through the suitcase. Then she squirms, signaling a wish, a need, to be put on the floor. She runs outside and barks at the thunder as if she wanted to scare it off.

I’m preparing for a trip. I stand, hands on hips, and my thoughts spin around the things to pack, including clothes, gadgets, medicine, and all that. Ultimately, my thoughts land on books I want to take with me, which brings about a much bigger question. It comes out of nowhere and floats amid undefined, vague thoughts. But once I single it out, it holds my attention firmly.

Here it is: what keeps me living in books, living in them wholeheartedly? I don’t mean in general. I mean now. What is the reason now? Has it changed since I was a child? And is that connected with writing? I have an uncomfortable vision of the future when, instead of a suitcase, I rummage through a few years’ worth of my writing and don’t find what I’m looking for. But what could I be looking for?

I think I’m looking for books that transcend their physical limits. Writing is black letters on white pages, to put it bluntly. But it’s the most banal way to look at it. What about those stories where writing resembles a video game? Or a well-crafted melody? Or that feeling in the stomach when descending from the swings?

(Some weekends ago, I found decorative, heavy swings in the center of a small city. I wanted to try. My brother pushed the swings so I could gain momentum. For a while, I swung high and, descending with a whoosh, thought: what combination of sentences could imitate this feeling? Then I was annoyed that I couldn’t engage in the smallest, silliest activities without thinking about sentences.)

Silliness aside, in order to give a certain feeling to the text—whether it’s swinging-induced vertigo or some other—I want to apply unconventional structures. Sure, contemporary life supplies new structures: I’ve seen a few books resembling chat rooms, tweets, or web pages. It’s easy to fall into their trap, thinking they’re hot and fun, and then bring their tediousness onto the page by mimicking them. I’ve read plenty of those. But I’ve also read Tess Gunty’s The Rabbit Hutch, one of the most inventive novels in the past few years. It fiddles with many different forms but has none of the tediousness I’ve mentioned.

The Rabbit Hutch is set in a small American town, Vacca Vale, that is lagging behind. Not to worry, big shots seem to shout: the town is about to be re-energized with an ambitious project. This project looms over the story as a massive, massive shadow. Tess Gunty paints Vacca Vale, a town on the brink of change, with minute care. She describes its paths and fields and establishments and also the history of Zorn automobiles, a key component of its rise and decay. She also paints the portraits of Vacca Vale’s people. Let’s take an adolescent girl, Blandine, who’s trying to free herself from her past and transcend her body. She lives in a housing complex called The Rabbit Hutch, and she’s the main character of the story—The Rabbit Hutch is very much her story—but she’s joined by an array of others who all have stand-out features.

I like ambitious writers who run the risky line of throwing too much into the mix. Whether The Rabbit Hutch has too much is probably a question of taste. In the end, all these complex characters, the town’s bleakness, the echo of the grandiose automobiles, adolescent explorations, heartbreaks, and violence are tied together. When I say it’s one of the most inventive novels I’ve read in the past few years, I want to say that it uses a mix of structures. There are excerpts from an online obituary page. There’s a section of drawings for a big reveal. There are short chapters looking into different apartments in the same housing complex or short chapters exploring interior worlds. And there are longer chapters unraveling the more complex threads of the story. I want to dedicate some time and analyze all the different maneuvers Gunty has taken, document them, see what I can learn.

The puppy returns and whines. Her ball has rolled too far under the table. While I work on retrieving the ball, she steals my shoes and starts chewing on them. I stretch my hand as far as I can; a sharp pang clutches my neck. There’s something wrong with the angle I positioned myself. I take the neon ball in my hands, rub my neck, and try to get her interested in the toy again.

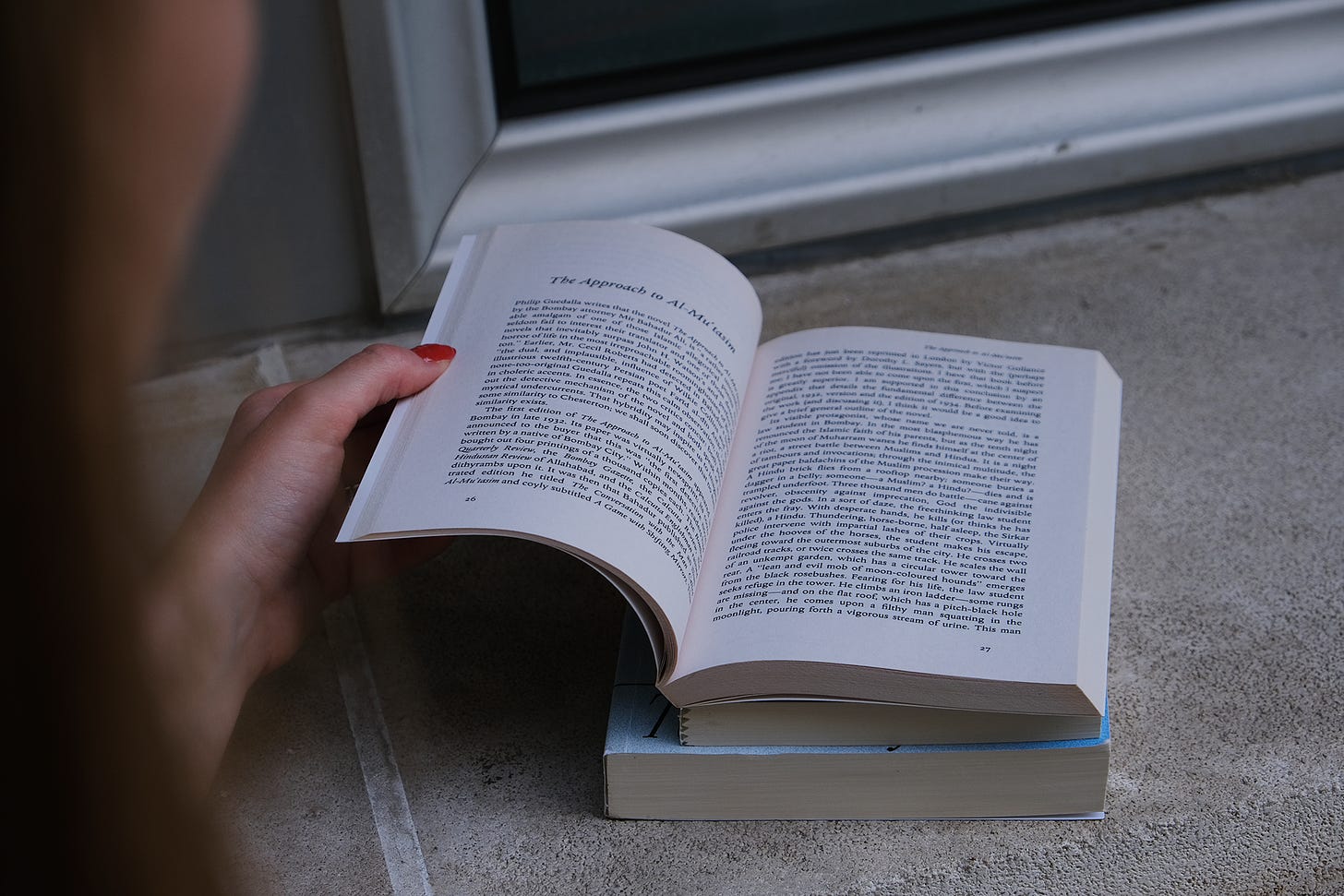

After some games and tea, I pick two dresses from my wardrobe and return to my reflections. The word “ambition” spins in my mind. Ambitious, that’s how I’ve always liked to think of myself, even if I’ve discovered people have wildly different interpretations of what it means. Books help sustain ambition, too. I remember Jorge Luis Borges and his Fictions I’d abandoned some years ago. I was spooked by his ambition, by how big and demanding his storytelling gestures were. Only a few stories in, I searched for a quick exit. I decided to wait for a moment when I was driven not by curiosity but by something more fitting to Borges's motivations.

This time recently came. After The Rabbit Hutch, I wanted to take a break from contemporary tales and pick up something otherworldly. Well, Borges. Borges’s stories are replete with mythology, allegories, enigmas. Whether they’re about an invented planet with its language and laws, or about a writer rewriting Don Quichote in the same words, or about the Library of Babel containing all possible combinations of all basic characters of the alphabet (“The feverish Library, whose random volumes constantly threaten to transmogrify into others, so that they affirm all things, deny all things, and confound and confuse all things, like some mad and hallucinating deity”), his scope eludes words. In his work, history copies history, and history copies literature. Dreams become objects, and objects become people. There’s the idea of infinity, overwhelming infinity. This transcends the ambition itself, whatever definition of it we might have.

What’s more, I want to say that Borges jokes with reality. He certainly takes it very loosely. The title Fictions suggests that, too. For example, Borges writes reviews of fictional books, which I find endlessly thrilling. Why? Well, sometimes I want to create fictional units, maybe fictional brands or newsletters, and then talk about them in my stories. This way, fiction would give me the green light, a cheat code of sorts, to work on things I wouldn’t have time to elaborate in real life. Because in a story, a snippet of an idea can represent the whole idea.

A puppy discards her neon ball and comes near. She sits down, looks at me. Her gaze can be so consistent, so unwavering, so un-puppy-like, that I can’t help but wonder what she sees when she looks at me. She would make a great companion in some weird adventure story, where we’d need both bravery and persistence, but we’d also have loads of fun.

Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet, have you heard of it? Seeing Carrington described as the “surrealist trickster” on the back cover is a good start. The Hearing Trumpet is a creation of whimsy and weirdness. I hadn’t read a book narrated by a 92-year-old lady before, and it was wholesome. The narrative is a bag of wonders and adventures, and if you poured things out of it, you’d get visions of Lapland (a lifelong dream of our heroine), a nursing home governed by a semi-oppressive self-improvement cult, searches for the Holy Grail, the narrator’s friend’s lilac limousine, and many more things. And if that’s not enough, there’s a short book within this book.

After The Hearing Trumpet, I was gripped with Carrington’s art, eager to discover everything she’s made: from her biggest work to barely-known crumbs, all mediums included. Carrington’s boundless artistic-ness enabled her to lead an unconventional life. I couldn’t lead such one myself, but at least I have sparks of her art to refer to and get inspired by. On that note, I want to read Surreal Spaces: The Life and Art of Leonora Carrington by Joanna Moorhead.

Finally, meandering through these examples, among the folds of my dresses and the puppy barks, I define my answer of what I look for in books now and what I'd want to find in that suitcase of my own writing.

I want writing to ooze like syrup. I want it to shine subtly like a star, shine among the mountains of the content generated every day, all that content filled with artificial sweeteners and quick forgettable bites. I want writing to be a crystal ball, showing things that have happened, will happen, could have happened in alternative scenarios. These books—The Rabbit Hutch, Fictions, and The Hearing Trumpet—are connected by unconventional structures, adventurous mood, and intense ambition, tinkering with reality and fiction. And so they transcend their physical limits in one way or another.

I continue living in books—living wholeheartedly in them—so I can see, learn, and have all that.

Love this piece, and as someone who dearly loves books I'll definitely be ruminating on that question: "what keeps me living in books?"

"Books help sustain ambition".

I couldn't agree more with you. Have you noticed, or has it happened to you, the more books you read toward the vibe that aligns with you, the more you want to write your own "black words in paper"? It sounds cliché but it's been happening. The hard thing is, finding the words to translate what you want to say.

And that is my personal predicament.

Your writing is beautiful and it feels soft and kind, with passion underneath moving the current. You found your own language. It is inspiring!

Fictions by Borges and Carrington's The Hearing Trumpet are two I am looking forward to read. Thank you for the little extra push to do it sooner! 💞