je lis trop: what I witnessed

march essay on a car crash, creative but fearful states, focusing on the present, watching the wheels turn, and advanced tax law

I was sitting in the backseat of my mom’s car in the hospital parking lot, waiting for her to return from an appointment. I might have had a book to flip through, something to read, some pictures to look at. Most likely, I was bored. At some point, I turned around to look at the street through the back window. I saw a car poised on the corner, waiting to make a turn. The street was empty; it was calm all around. I guess it was waiting because the driver was scanning the area to make sure it was safe to turn.

Finally, it accelerated, the whole body pivoting to the left, in a movement that seemed swift but also unstable (it was an old car). But in the mid-turn, a new character sprung onto the scene, as if an animal that had been lying in the shadows: another car flew in from the side street. It crashed into the car I’d been observing, raising the dust, pieces of metal flying off in the air.

Whenever I think back to that scene of two mingled cars and the creeping silence, I don’t remember how I felt. I observed the scene as if it were lifted from someone else’s story and pasted onto that uneventful street. I took it in and returned my gaze to the hospital in front, waiting for my mom to emerge. I might have been disturbed. I should have. I couldn’t have been more than six years old at the time. I knew I had witnessed something surreal but I didn’t know what that word meant. Yet.

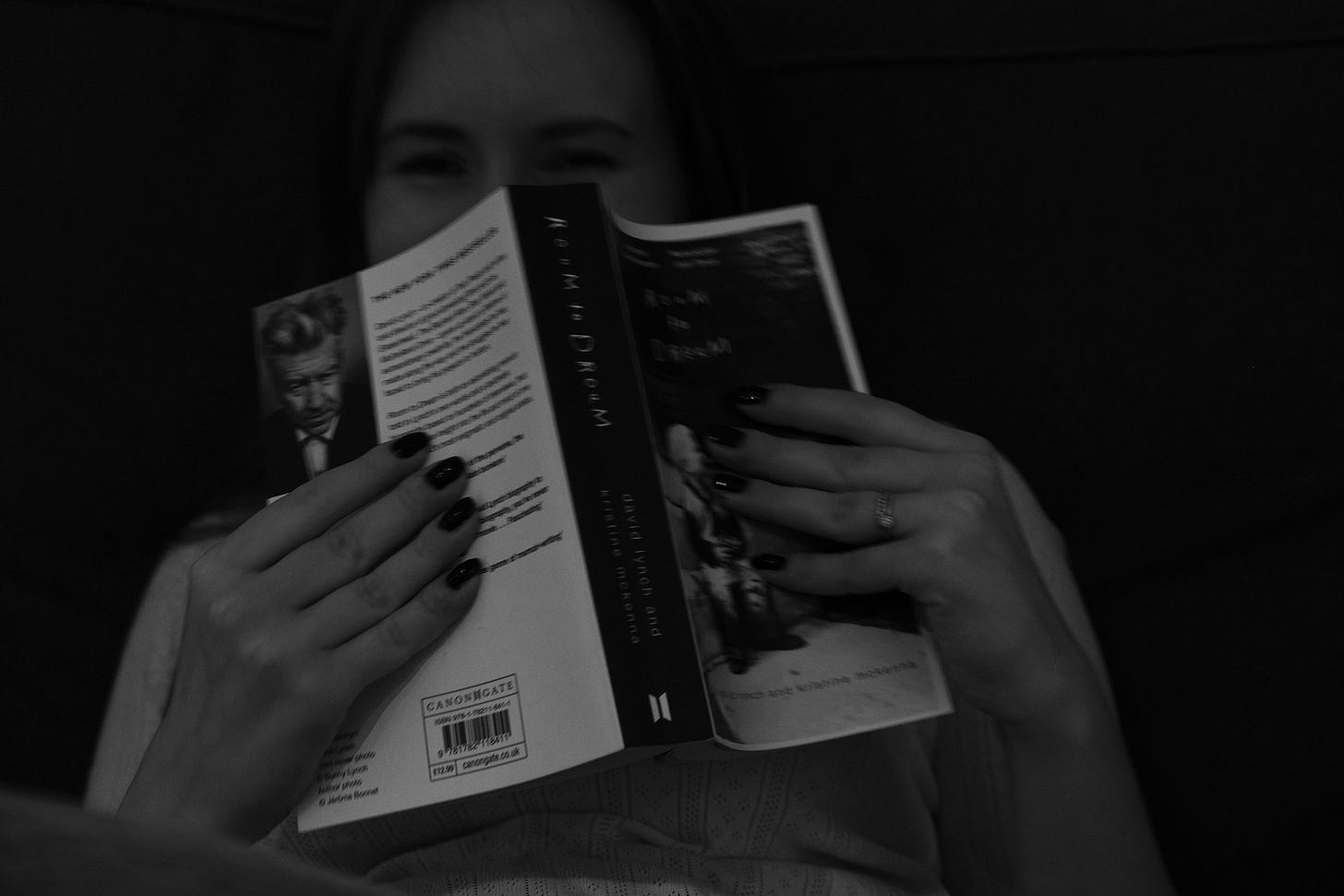

I experienced something similar while watching David Lynch’s movies, where I saw uncanny things. I wouldn’t be able to process them while watching, so I would return my gaze to daily life, but those sights and ideas would resurface day after day, and I would continue probing them. Or perhaps they would continue probing me. After I saw Mulholland Drive, it appeared in my dreams for three nights. And I had a knot in my stomach after watching Lost Highway, thinking about how twisted and scary and hypnotizing this movie was.

What was this knot in my stomach? What were those uncanny things that I continued probing? David Lynch and Kristine McKenna’s Room to Dream answers this question to some extent: “We live in a realm of opposites, a place where good and evil, spirit and matter, faith and reason, innocent love and carnal lust, exist side by side in an uneasy truce; Lynch’s work resides in the complicated zone where the beautiful and the damned collide.” I am attracted to his work precisely because of the dualities. Being wrapped in a blanket with a book in my hands, waiting for my mom to return, and knowing that such an event as a car crash is possible in the outside world, is one of the earliest and most powerful examples of duality I have experienced.

But what I want to say about Room to Dream is that it was an event in my life. There was a two-week period when I was overcome by extreme self-doubt. I was dizzy and shivered before presenting (or even talking about) my work, my stomach turning so violently as if it was sensing imminent danger. I don’t know what was going on with me then, but it was a scary state to be in. Such a state, left unchecked, could easily turn into a sad helpless thing. The book brought me back to the realm of ideas, where everything has potential and nothing is fixed; it’s just me, playing with concepts. Pure consciousness, as Lynch would say.

The chronological retelling of events in Room to Dream is fitting to the biography genre but it is also enriched by Lynch’s commentary, which gives a twist to the conventional registration of what happened and what other people said. Of course, he talks a lot about living a creative life and gives bits and pieces of helpful advice. He mentions catching ideas and I wonder who can guarantee I will catch ideas? I don’t have a template to operate on, and that's a scary thing to realize for someone who likes to be organized. I noted a small phrase in my diary: tune in to the small things and, when the time comes, you will know how to connect them.

Lynch’s thoughts—especially on meditation—also hint at how to have at least some mastery over one’s mind. Having such mastery could, perhaps, help me with another question: dealing with the rapid passage of time. This unavoidable fact of life troubles me. One of the ways to dull the discomfort is to follow the present moment very closely. I have come up with some techniques, for example, trying to etch a moment so deep in my mind that it never, ever leaves it. But if I try too hard, I might become detached, as if the sights before me were on the cinema screen, and I was only a spectator. How to be effortless but also laser-sharp in registering one’s reality?

Clarice Lispector’s Água Viva echoes my worries. “The next instant, do I make it? Or does it make itself?” I have read this tiny book of meditations three times, and I will be reading it as long as I continue creating. What does she do with words? She uses them to reach whatever is beyond thought, to describe her intense fascination with animals, to perfume herself, to paint flowers (roses, violets, carnations), and to take photos of the fleeting instants. Most of all, she forms tiny throbbing pictures that pass in front of my eyes in all their colors. But they don’t blind me to my reality, quite the contrary. As I’m writing these lines, I also see a glass of water, a brown table, a sparkling mirror. I can taste that my coffee is already cold. I feel tiny swirls of wind coming from the open window and I respond to a woman who wants me to help her find an electric socket to charge her phone. And I do that with my full attention.

The present moment is a dominant theme in Água Viva. It provides many convincing metaphors, but here’s one that dazzles me the most: “The present is the instant in which the wheel of the speeding car just barely touches the ground.” I always think of it when I watch passing cars through the bus or a taxi window. I see their turning wheels, and I count the passing instants. That's how life moves.

It should be obvious by now that living in the present is about paying attention. Accordingly, I want to bring up David Foster Wallace’s Something To Do With Paying Attention. It slotted perfectly into those days when I most intensely wondered about the attention. This short novella has been described as a story where a man talks about his life-changing encounter with advanced tax law. This fact doesn’t prepare you for anything; the first words of the narrator (“I’m not even sure I know what to say”) don’t signal what a powerful story is yet to come, a story where nihilism and sadness quietly transform into something beautiful.

Let me tell you how I experienced the story. The first page was akin to sitting down in front of this man who would tell me something about his career. I started listening. At first, he talked a lot about his parents, disappointments, and the emptiness of it all. But slowly, almost imperceptibly, the story got more riveting because of his honesty and the way he reasoned and expressed his ideas. He mentioned something about attention, something about being alive in daily life rather than functioning on a ‘robotic autopilot’. Even though his alertness to life was drug-induced, being aware and staying so became important. Awareness conferred meaning, overruled his old ways of existing, and, combined with the influence of the advanced tax law, brought urgency to his life. His story left me in awe, while Wallace’s writing left me stupefied. It is a model I can look up to while borrowing elements from Lispector’s mysticism and exploring Lynch’s ideas about creativity.

I continue learning how to live with dualities, how to be alert, and how to etch moments into my mind. I continue learning how to catch ideas, how to perfume them, and give them out to the world in the precise form I intend to. I continue witnessing.